All the prints illustrated on this website are colour prints from multiple woodblocks. The category of Japanese woodblock print known as surimono, meaning literally ‘printed thing’, was distinguished from most of the other prints in several ways: surimono were privately commissioned and distributed rather than being issued by a commercial publisher; they were printed on thicker paper hosho (‘presentation paper’) which facilitated special printing effects; and they were consistently adorned with poems that played games with the links between verbal and visual imagery. By comparison with run-of-the-mill commercial issues, surimono were a luxury that displayed the wealth and taste of the individual or individuals who commissioned them. For the artist they represented high-profile commissions executed in close consultation with the leading connoisseurs, poets and actors of the day.

Kunisada was actively involved in the production of surimono from the late 1810s to the middle years of the 1830s, when an economic crisis brought a halt to such indulgent luxuries. It is estimated that he designed at least 300, most of which were devoted to kabuki actors. He exploited the richness of the format to produce prints of extraordinary elegance and opulence. His surimono include many of the finest prints he designed in this period, which coincided with the flowering of surimono in Edo (present day Tokyo), particularly in the square shikishiban format. Like all surimono formats, shikishiban was a division of the standard hosho sheet: a hosho sheet divided into six forms shikishiban sheets. Most shikishiban prints were kyoka surimono, commissioned by members of the large kyoka (‘crazy-verse’) poetry groups (gawa) or smaller poetry circles (ren), who would swap surimono at poetry gatherings. Other individuals commissioned surimono as private greeting cards or mementoes of particular events for distribution among their friends or clients. They were often produced at New Year, with suitable poems auguring good luck accompanying seasonal spring imagery or symbols of longevity. Kabuki actors commissioned surimono to distribute among their sponsors and fans. The fans themselves also commissioned surimono to extol the virtues of their favourite actor. In Kunisada’s surimono of actors, a particular performance or role is often commemorated, just as it is in the commercial prints.

The production of surimono was more complex than that of standard commercial prints; accordingly the name of the ‘producer’ or ‘printer’ is sometimes recorded on the print. In some cases there were even specialist studios headed by artists, which produced surimono for other artists. For instance, the studio of Kubo Shumman produced several surimono to Kunisada’s designs, and the Shumman seal appears on the prints.

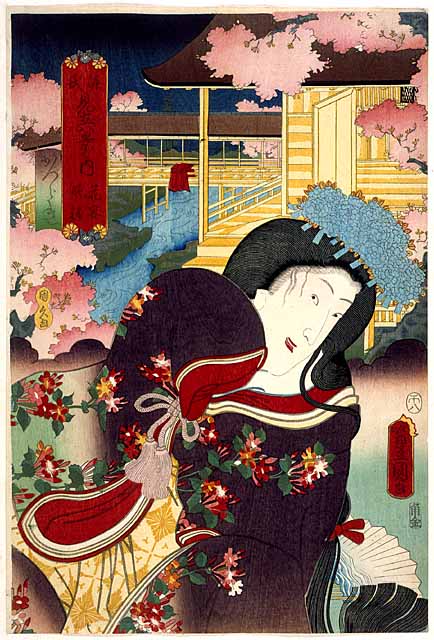

There were various types of special printing on surimono: blind embossing of the paper from specially cut blocks without ink (karazuri), using ivory or bone to press precise patterns into the paper; embossing the surface of the paper with the texture of a textile glued on the block (nunome-zuri); burnishing the surface after printing to make it glossy (tsuya-zuri ), especially in black areas to suggest a glossy wig or black silk collar, or to introduce an extra pattern into coloured areas; metallic pigments, often brass, which reflect light; pigment sprayed through a straw to give a speckled effect; white pigment splashed or flicked with a brush onto the printed surface, often to depict snow or the spray of water; pigment sprayed through a bamboo straw to give a speckled effect. Many of these effects are only visible when the surimono is held in the hand and moved around in the light. They tease the eye, delight and surprise, in the same way that the poems and images delight and surprise as their various allusive meanings are teased out.

Costly printing effects were also used in the best impressions of the commercial prints produced towards the end of Kunisada’s career in the period when he was using the Toyokuni signature. In addition, materials and techniques that had been used in the lavish printings of prints and books at the end of the previous century were also used, such as the sprinkling of mica dust (kira) to sparkle in the light, and the addition of animal glue (niwaka) to the burnished black to give the effect of lacquer. The prints sometimes bear the name of the block-cutter or printer as well as the artist. These luxury impressions of Kunisada’s prints of the 1850s and 60s must have been substantially more expensive than the impressions of the same subjects that were printed (presumably in much larger number) without the special printing effects and on thinner, cheaper paper. Presumably they were aimed at a more sophisticated clientele, perhaps collectors who would keep these luxury prints in albums rather than paste them on walls and then discard them. These later, luxury prints often come quite close to surimono in effect, particularly in the actor portraits that include poems, and they were evidently aimed at collectors with comparable wealth and refined taste.